Part Two: as a Chinese jar

So, a bit more about 12 Henrietta Street and why I called this post Pictures from an Exhibition. Two weeks after shooting there I was back to see an exhibition called ‘as a Chinese jar’ by a young artist Roisin Power Hackett. The title comes from a line of a poem by TS Eliot, Burnt Norton.

“Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness.”

On her website Power Hackett says “These lines speak of the patterns on a Chinese jar and how they repeatedly seem to move, despite being fixed motifs. This can be taken as an example of the rhythms and energy in life and the world”.

Further: ”In her paintings and performance Róisín questions peoples’ relationships with their surroundings, depicting an abundance of intricately patterned wallpapers or rugs and blurring the edges between the person, their clothes and their environment…

She portrays historical characters, both real and fictitious, as well as her peers. Her characters blend into their backgrounds, absorbed and influenced by their respective societal norms, they either almost disappear or fight to be seen and heard”.

“In ‘as a Chinese jar’, Róisín focuses on the power relations between the genders as well as between the rich and the poor. Her work highlights how women are regularly oppressed, pressured into submission and made to fade into the wallpaper”.

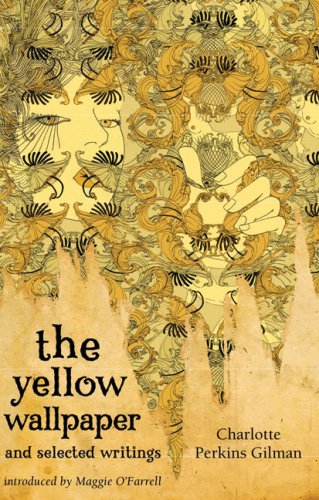

This would suggest to me a visual equivalent of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s claustrophobic feminist gothic The Yellow Wallpaper.

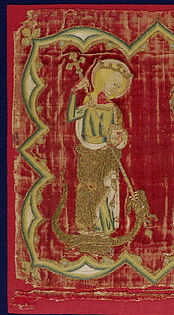

The Red Room – actually more a madder rose if you want to be precise – is high-ceilinged and was slanted with sunlight.

In the centre of the room red wool hung from two chains attached to the ceiling, and attached to the wool were red booklets of Power Hackett’s poetry and a green label that said “Read Me”.

The artist was sitting in a corner of the room, partially covered by a repeat pattern fabric that also wallpapered one wall from dado rail to floor.

Most of the paintings are oil on wallpaper, although the wallpaper isn’t always apparent. Many were very lovely. Ironically, however, they work better as decorative pieces than as polemic. I’ll admit I didn’t see the performance part of the exhibition (Unless the artist’s monosyllabic presence was performance?) so perhaps I don’t have the full story, but I got no sense of struggle or silenced voices from the works.

The more contemporary portaits in particular seemed almost jolly, as if everything is fine now and the feminists have won.

Should this matter? Is it not enough to see lovely paintings in a lovely room? Well, given that Power Hackett’s intentions are so noble, yes it does matter.

Roisin Power Hackett is a very promising artist, and here is a highly resonant way in to women’s lives past and present.

Are women complicit in their own silencing? Where do domestic or private interiors fit in to all this? Are they the female voice given form or the method by which we gild our own cages?

I’d be really eager to see her develop her themes; to go really deep and let her paintings howl. In the words of TS Eliot again: “So the darkness shall be light, and the stillness the dancing”.

I wish I didn’t know that this is a painting of Anna Karenina from the 2012 film directed by Joe Wright

12 Henrietta Street was open to the public as part of the Open House weekend.