I only read recently of the death of Rozsika Parker, and having intended to review The Subversive Stitch for months am finally galvanized into doing so.In a glowing obituary in The Guardian Ruthie Petrie describes Parker as

“A feminist, art historian, psychotherapist and writer. In all her work is a stitching-together of the themes that occupied her: women’s struggle for recognition within the art establishment; a challenging of the division between fine art and the decorative arts; the tensions, sometimes productive, sometimes destructive, in women’s creative work.”

The Subversive Stitch was first published in 1984, and was revised and re-issued to coincide with the V&A’s Quilt exhibition (see below). This revision has incorporated a new introduction which covers, briefly, the work of Louise Bourgeois, Tracey Emin – of whom Parker clearly does not approve – and others.

It is, without doubt, a Feminist History and with all due respect to the Sisters, it is within this framework that I find it flawed.

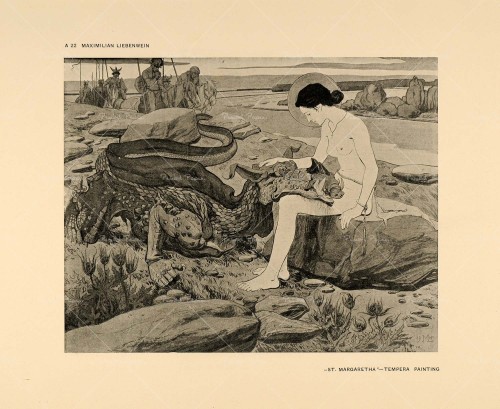

Parker is brilliant on the particularly bonkers brand of misogyny peddled by the Church. For instance, during the Middle Ages St. Margaret was one of the most popular of all the saints and martyrs as the patron saint of childbirth. She was thrown into a dungeon for refusing to denounce Christianity and was swallowed by the devil in the form of a dragon. She escaped because her crucifix caused the dragon’s belly to explode. Having inspired 5,000 pagans to convert she was beheaded. Her last request to God was that pregnant women who prayed to her should be granted an easy birth and a healthy child.

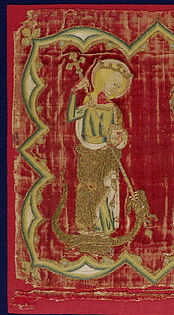

St. Margaret gets medieval on a dragon’s ass. It’s a metaphor for childbirth. (Detail of a panel from a burse held in the V&A Museum, made in England 1320-40)

However, because God has cursed women to bring forth their children in pain (Genesis 3:16) the depiction of any intercession, whether by midwives or by patron saints was prohibited. An interesting anomaly developed where a sanitized version of St. Margaret’s story existed in writing, while embroiderers continued to decorate priests’ chasubles with the kick-ass Margaret they and other uneducated churchgoers knew.

By the mid-nineteenth century – during the Victorians’ Gothic revival – St. Margaret had been diluted into an unrecognisably meek version of herself.

Parker also describes the evolution of embroidery from Guild-protected professional work to work that was done at home, for love or out of duty rather than for money. This change occurred during the Renaissance when, as is the case now, it was a luxury to have a stay-at-home wife. And if she could produce luscious bedding, curtains, wall hangings et cetera, then so much the better:

“Embroidery combined the humility of needlework with rich stitchery. It connoted opulence and obedience. It ensured that women spent long hours at home, retired in private, yet it made a public statement about the household’s position and economic standing”

She explores the changing fashions in embroidery from representations of biblical or mythological scenes in the Middle Ages; to the Elizabethan riot of flora and fauna; through Seventeenth Century samplers which emphasised the technical skill of the seamstress rather than the breadth of their imagination, and on via the Industrial Revolution, when pastoral scenes were at their most popular and biblical scenes saw a revival.

There is a fascinating story to be told about and through embroidery. The problem I have with the book is that it is Feminism first, and history second. Parker has grouped her chapters thematically so just as you’re getting to grips with womens’ position in Guilds (sometimes in charge, sometimes not), she will introduce some example of paternalistic Victorian perfidy. Usually she refers back to her original point, but it can be at least a chapter before she does so. Often too in this later expanding on a stridently made original point the facts reveal a far more ambiguous truth.

This combined with a justifiable anger has affected her ability to marshal the facts.

A simple narrative history would allow her readers to come to their own conclusions – namely that history (or rather herstory) sucked – without feeling we were on the receiving end of a rant.

I feel guilty criticising The Subversive Stitch because Roszika Parker has passed on, and I was taught not to speak ill of the dead. Also her generation of feminists really made my lot look good a difference in this world.

The Subversive Stitch is an important but ultimately difficult read. One perhaps for the academics and gender studies crowd rather than the practitioners (no offence).

Pingback: The Subversive Stitch – Rozsika Parker | SewWitty